More evidence is in that hallucinogens may have some value in treating some mental disorders, particularly anxiety and depression. This post at the Smithsonian covers the latest research, in this case into the use of psilocybin (the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms) to ease anxiety.

But the article also covers previous research into the use of psilocybin to treat depression.

The highlights:

In 2011, a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry by researchers from UCLA and elsewhere found that low doses of psilocybin improved the moods and reduced the anxiety of 12 late-stage terminal cancer patients over a long period. These were patients aged 36 to 58 who suffered from depression and had failed to respond to conventional medications.

We do know that soon after psilocybin is ingested (whether in mushrooms or in a purified form), it’s broken down into psilocin, which stimulates the brain’s receptors for serotonin, a neurotransmitter believed to promote positive feelings. . . .

But another, and less obvious, question, is: Why has this research not been done before? After all, we have known about psilocybin for millennia, and about LSD for over half a century.

This question, unlike the one about psilocybin's neurochemical action, is easy to answer. This research has not been done, at least not in the US, due to irrational, hysteria-driven drug laws.

This article in PopSci explains things fairly well. In brief, researchers in the 1950s and 1960s WERE looking into therapeutic uses for psychedelics. But research ground to a halt after Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act. That is, research into medical uses of these substance fell victim to what would later be known as "the war on drugs."

The "war on drugs." Or, as it is better known among those familiar with that "war's" toll, "The War on (Some Classes of People Who Use Some) Drugs".

Because drug laws in the US have always been irrational at best, and downright racist at worst. Behind nearly every drug law is a simmering cesspool of social and/or racial anxieties. The first law in the US dealing with a psychoactive substance was San Francisco's 1875 law directed against opium dens. As that site notes:

The ordinance was aimed specifically at Chinese smoking opium, not at the medicinal opium regularly consumed by whites. The Chinese had brought smoking opium with them in the earliest days of the gold rush. The habit caused little offense at first, until anti-Chinese sentiment swept the state in the mid-1870s.This thread of race fears and prejudice is practically a constant throughout the history of US drug laws. Later in the 19th century William Randolph Hearst, the Rupert Murdoch of his day, used his tabloids to stir up fears of Chinese (the "Yellow Menace") with tales of white women succumbing to Chinese men and opium.

Laws against marijuana were passed in a frenzy of racism against Hispanics and "Negroes." (For a great taste of what white fright sounded like in the early 20th century, you can't beat this quote: “Marihuana influences Negroes to look at white people in the eye, step on white men’s shadows and look at a white woman twice.”) In Texas, a legislator claimed, '"All Mexicans are crazy and marijuana is what makes them crazy."

Likewise, in the press cocaine was associated with "Negro Cocaine Fiends" who were said to murder, go insane, and assault white women under its influence.

Far too recently we had the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, passed during the hysteria about crack cocaine. The law mandated acute disparities in sentencing: punishments for possession of crack, mostly used by African-Americans, were far more severe than punishments for possession of similar amounts of cocaine.

And, given the systemic racism underlying the criminal justice system, it is no suprise that even today enforcement of anti-marijuana laws still disproportionately targets African-Americans, who were "nearly four times as likely as whites to be arrested on charges of marijuana possession in 2010, even though the two groups used the drug at similar rates, according to new federal data".

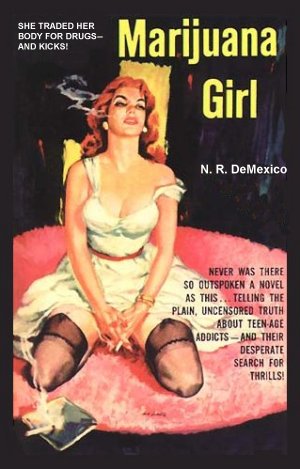

(Just for fun, and since I'm a fan of pulp novel covers, it is worth pointing out that the hysteria over drugs and female purity could be expressed somewhat independently of explicit appeals to racial fears:

|

| Image found here |

Though it is worth noting that in the narrative of Marijuana Girl, her journey as fallen girl passes through jazz clubs! And the reader certainly would have known what sort of skin colors she was likely to encounter there!)

(One of the bitter ironies of all this is that while one hand of the US government was clamping down on drugs, largely in response to racist fears, its other hand was helping out in the trafficking of heroin and cocaine.)

So maybe I've given you more of that history than is strictly necessary for my purpose here, which is to emphasize that our drug laws have never been based on rational assessments of risks and benefits. Which is why it is especially annoying that we have lost some 40 years of research into the potential benefits of psychedelic drugs. The act that outlawed the major psychedelics (LSD, psilocybin, peyote) in the US was passed in 1970 (the Controlled Substances Act), and as you might easily guess it was more a response to social fears, in this case the fears of the 1960s youth movement than to scientific evidence. In the CSA the psychedelics were all classified as Schedule 1 drugs: substances that were held to be highly prone to "abuse" (often via addiction), that had no medical use, and that were too dangerous to use even under medical supervision. Those are the official criteria. In practice, however, those criteria are not adhered to particularly well: drugs often end up as Schedule 1 drugs not so much because they meet the official criteria but because they get used recreationally by the wrong kind of people. Compare, for example, the legal status of marijuana, a Schedule 1 substance, to that of alcohol, which is excluded from the CSA's definition of "controlled substance." This dynamic is very much at work in the case of psychedelics, which are neither addicting, nor too dangerous to be used under medical supervision, In fact, the naturally occurring psychedelics have been used in numerous cultures for thousands of years. These drugs are categorized as Schedule 1 because they were being used by the wrong kind of people in the 1960s—by people who were seen by Middle America as a threat to the social order. And regarding the criterion that Schedule 1 substances have no medical use: this would quickly become a self-fulfilling prophecy. By classifying them as having no medical use, the law ensured that no medical uses would be found for them, since they were decreed to be too dangerous to be tested (administered) under medical supervision.

And during that 40 year time, countless people have suffered from depression. Many of them committed suicide, while far more slogged as though half-dead through days, months, years of unspeakable psychic torment. Pointless pain piled atop pointless pain. We can't say for sure that psilocybin is a viable treatment for depression, though it does look promising. BUT if it turns out to be effective, a great deal of needless suffering might have been alleviated had it not been for bad laws that were shaped by America's deeply entrenched, irrational social anxieties rather than by reason, science, and compassion. Makes me wanna holler.

Vaguely related memes:

"For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

—William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

"Remember what the dormouse said. . ."

No comments:

Post a Comment